Text by Marc Graser

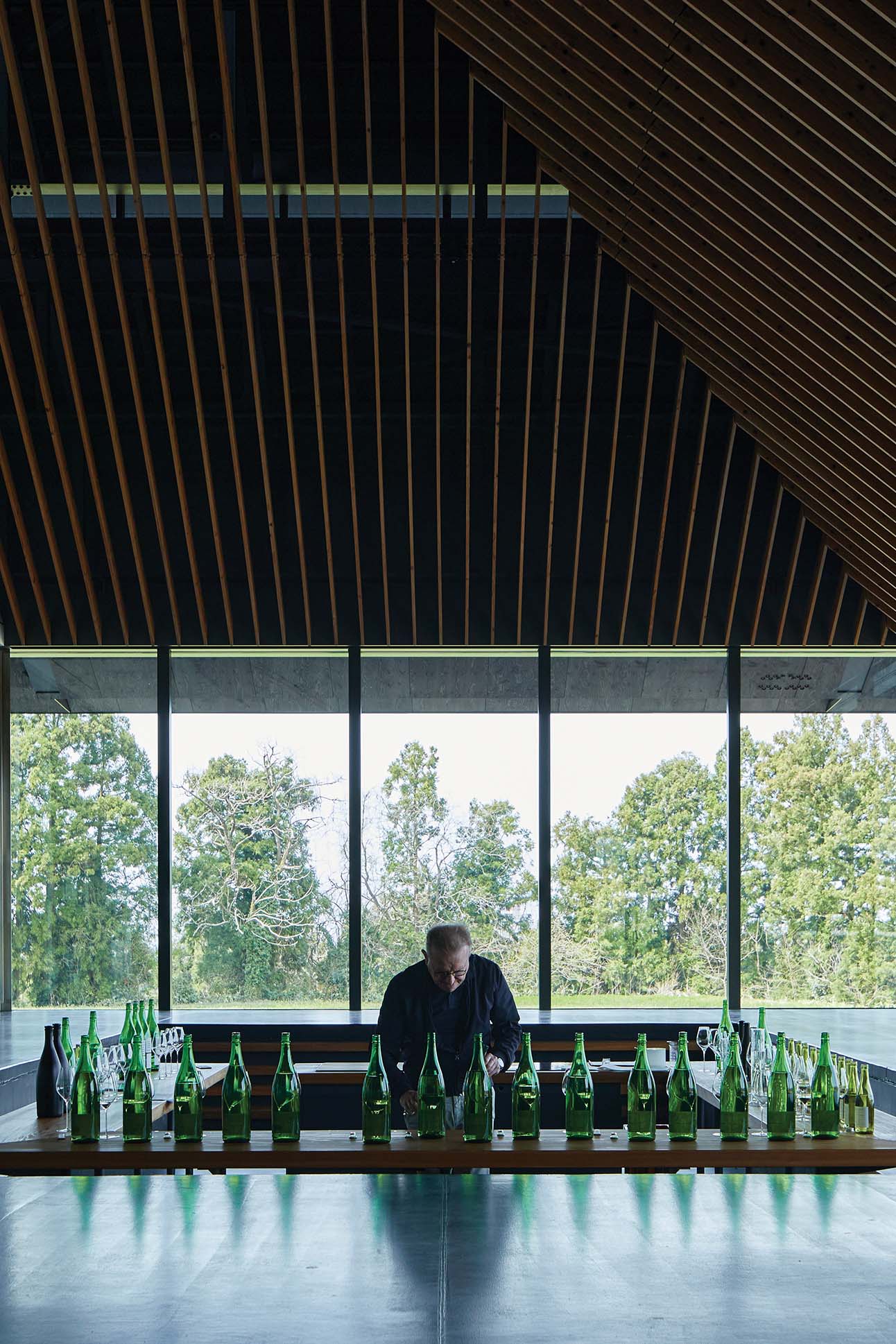

Images courtesy of IWA

Richard Geoffroy watches intently as you sip his sake. It’s surprisingly light, smooth, crisp and complex, sweet and citrusy with a nose of white pepper. It doesn’t have that lingering hint of licorice that fermentation can sometimes produce. Instead, this is more like a refreshing white wine you might enjoy on a hot summer day. It’s still sake, but it’s also something else. There’s a nuance that takes it to another level. It ultimately makes you question everything you know about Japan’s most recognized spirit.

“It is sake. I want it to be sake,” Geoffroy says. “If I were told it’s not sake, I would be devastated. So embarrassed.”

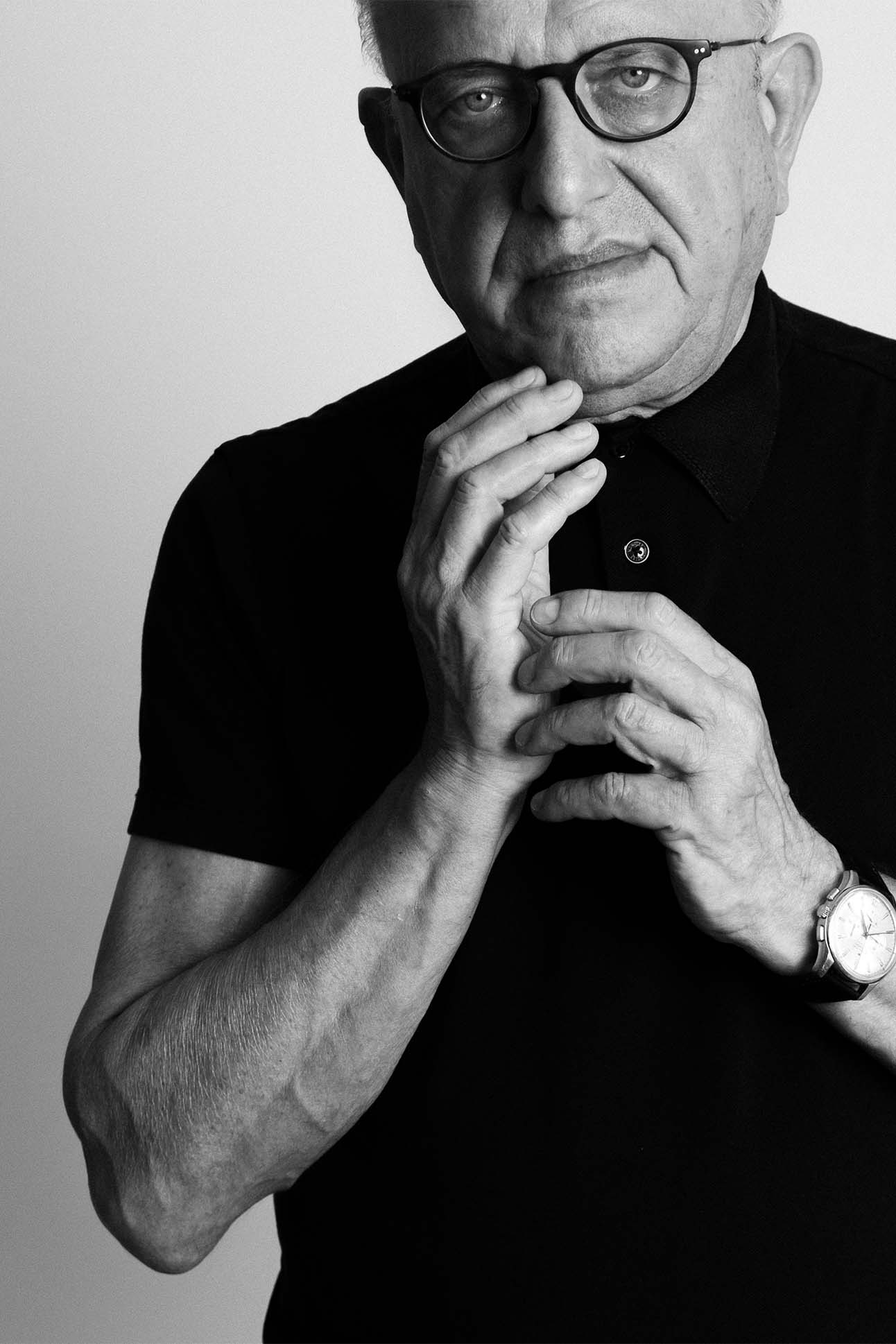

Geoffroy, 70, has nothing to be embarrassed about these days. After spending 28 years making Champagne as the chef de cave at Dom Pérignon in France (his family is also in the winemaking business), he is pursuing his newest passion as a brewer of sake in Japan.

After just three years, bottles of Geoffroy’s IWA 5 have captured the attention of an industry that has stuck with tradition as consumption has waned.

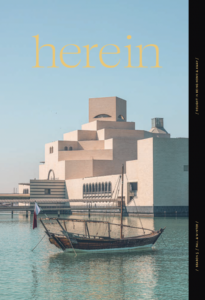

IWA’s building was designed by renowned architect Kengo Kuma.

Sake is typically brewed with water, rice, koji (a type of mold also used to make miso and soy sauce), and yeast. Where each element comes from and how it’s processed impacts the final flavor, which can range from fruity to full-bodied.

But Geoffroy did the unthinkable and used his French winemaking techniques to blend 20 different sakes, three rice varieties, and five yeast strains to “introduce an element of newness within the frame of something familiar,” Geoffroy says. “It has a strong foundation of where it’s from.”

The beauty of Japan is that when people disagree with you, they don’t tell you. But Geoffroy instead found a following among an elite fanbase, with bottles of IWA 5 being gifted to the country’s royal family and poured to premium class passengers on All Nippon Airways (ANA) flights to and from Japan.

That’s a huge honor for a Frenchman who has been visiting Japan since 1991, and always understood his place as an outsider.

“I’m not Japanese,” he says, “but I want to be accepted. I’ve been a visitor for a long time. I don’t want to be a visitor anymore. I want to be an economic contributor.”

To do that, Geoffroy knew he had to establish firm roots in Japan. He built his brewery in Tateyama, a small town near Toyama on the Sea of Japan coast, and hired sake master Ryuichiro Masuda to bring his vision to life. He’s hired dozens of staff from the local area. “People see that we’ve invested so much,” Geoffroy says. “We are a part of the community.”

Design has always been important to Geoffroy. “Aesthetics drive everything in Japan,” he observes. “It’s thought over, it’s thought out, nothing is random. It was important to deliver that dimension of aesthetics without being a cliché.”

Kengo Kuma, one of Japan’s most internationally renowned architects, designed the brewery’s dark, sleek, modern but traditional structure made of charcoal wood known as yakisugi, and topped with a steel roof. Kuma designed the Japan National Stadium for the Tokyo Olympics, as well as Marriott’s EDITION hotel and residences in Tokyo’s Toranomon neighborhood, and hotel in Ginza.

Influential Australian industrial designer Marc Newson, nearly as big of a fan of Japanese culture as Geoffroy, developed the look of the sake’s distinctive dark brown, matte glass bottle, which creates a cohesive connection to the architectural aesthetics of the brewery.

The tools and ingredients used to make sake are as delicate as the drink itself.

There’s also a reason behind the three letters of the brand’s name. Sake brands are difficult for foreigners to recall, Geoffroy says. “Three letters are about as long as people can remember.” The five is the universal symbol of harmony and represents union. “It’s my way of saying it’s blended sake.”

After years of being overshadowed by wine, sake is finding a new fan base around the world—2,500 years after being first introduced in Japan, where 95% of it is still consumed.

It couldn’t come at a better time. A younger generation of Japanese no longer drinks sake. And production has declined by two thirds over the past 50 years.

Yet while consumption is declining in Japan, sake sales are surging in the United States and elsewhere. Exports from Japan more than doubled in volume from 2012 to 2022, to nearly 36 million liters, according to the Japanese Sake and Shochu Makers Association, with the U.S. consuming more than nine million liters per year, up from just under four million liters during that same period.

Younger consumers are willing to try something new, especially those who have visited Japan and are coming back with tastes for the foods they’ve sampled. More than 2.2 million Americans visited Japan in 2019, up from 900,000 in 2010, according to JTB Tourism Research and Consulting. At the same time, sake is being poured by more bars across the U.S., making it less reliant on food experiences. Champagne sales started taking off when consumers started drinking it more socially, or to celebrate moments. Sake is still mostly consumed with a meal.

Sake is an acquired taste, and Geoffroy knew he had to make it more palatable. After many years of experimentation, he concluded the only way to accomplish that was to make it balanced and complex. That meant blending, something that’s long been done to make Champagne and wine. Most sake brewers, however, have operated independently and didn’t collaborate. And mixing sake is highly demanding technically.

To achieve balance, Geoffroy had to rethink how his sake could pair with international cuisines, not just the delicate flavors of Japanese dishes. Think spicy Chinese, bolder, fattier Korean, and rich French dishes. “It’s not shy,” he says of the resulting sake. “It’s so versatile. You can throw anything at it.”

The right sake requires amplitude. If it’s too dry, it’s difficult to balance bitter and sour elements. Where the dissolve and succession of sensations can seem too smooth with most sakes, it was important for Geoffroy to create one that didn’t transition so seamlessly where the experience ends up being almost flat. “Everybody was telling me to make it dry, but too dry is one dimensional,” he says. “In the end, it’s about emotion—the transition from one sensation to another.”

Geoffroy believes in the future of sake. After nearly three decades at Dom Pérignon, he could see storm clouds on the horizon. Global warming is taking its toll on the quality and amount of grapes grown for the wine industry. And strict regulations are making premium wines more expensive to produce and sell, significantly impacting profit margins. At the same time, global demand is high, relative to supply, which is inflating prices, driving consumers to consider sipping something else.

Sake’s success isn’t impacted by those same challenges. Its ingredients are easier to come by; it’s a matter of what you do with them. “Sake is way more about processing than sourcing, which makes sake so modern,” Geoffroy says.

“This project is bloody ambitious,” admits Geoffroy, who will continue to stretch what sake can be. He currently has three variants of his sake, but wants to add new layers of complexity with each assemblage he produces.

To grow the IWA brand, Geoffroy knows he needs to convert wine drinkers to sake. “One hundred percent of sake drinkers are champagne drinkers,” Geoffroy says. “And now I want to turn that around and make 100% of champagne drinkers sake drinkers.”