Text by Timothy A. Schuler

Images courtesy of Studio Gang

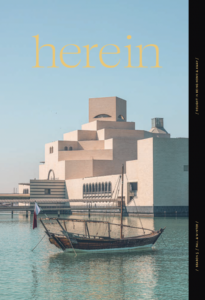

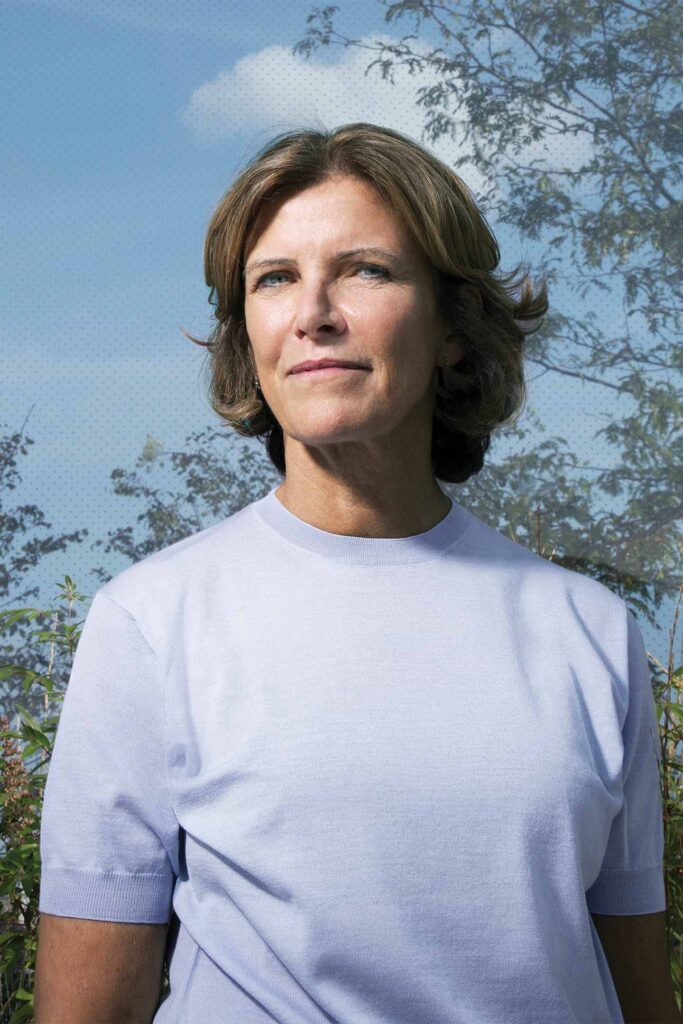

Historians of the future will list their names: Daniel Burnham. Louis Sullivan. Mies van der Rohe. Jeanne Gang. Over the past decade, the MacArthur fellow and founder of Chicago-based Studio Gang Architects has materialized as one of the most original voices on today’s architectural scene and solidified her place among the pantheon of visionary architects who called Chicago home.

What began as a small but ambitious practice of one has grown into a collective of more than 200 designers in four offices: Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Paris. Today, Gang is best known for buildings that, without any moving parts, feel kinetic. Chicago’s Aqua Tower sports rippling, white concrete balconies that give it the impression of a waterfall frozen in motion. Completed in 2010, it was the tallest building in the world designed by a female architect until Gang beat her own record in 2020 with Chicago’s St. Regis tower, home to The Residences at The St. Regis Chicago. The WMS Boathouse along the Chicago River features sawtooth roofs that evoke the graceful rise and fall of a rowing team’s oars. And One Hundred, a 36-story condominium tower in St. Louis, features repeating volumes of canted glass, which, like buds on a stem, seem perpetually about to bloom or unfurl.

This formal inventiveness is not about creating architectural drama for drama’s sake, or about winning accolades. For Gang, the daughter of a civil engineer and a part-time librarian and quiltmaker, architecture is a public art. “Whenever you put something onto the Earth, you’re putting it in front of everyone,” Gang says.

Gang’s consideration of a building’s impacts extends well beyond the eventual occupant, beyond even a city’s human inhabitants. For years, she has been at the forefront of a generation of architects exploring how buildings and cities can address the climate crisis, from reducing carbon emissions to actively supporting urban wildlife. “I’m interested in how architecture can work together with the environment to enhance biodiversity,” Gang says.

An avid birder, Gang is particularly interested in bird-friendly design. For nearly 20 years, she has been vocal about the fact that buildings—and especially tall, transparent, glass towers—kill up to a billion birds each year. The danger is exceptionally acute in cities like Chicago, she says, which sits practically in the center of the Mississippi flyway, a major migratory corridor for many of North America’s native bird species. For the studio’s faceted Solar Carve tower in New York, which rises next to the city’s famed High Line and is also located in a major migratory flyway, Gang used glass with low reflectivity and a bird-safe frit pattern to reduce bird strikes.

As is often the case, when it comes to urban habitat, the solution to one problem brings problems of its own. For instance, the larger and more ecologically sound a green roof is, the more likely it is to attract birds and, if it’s surrounded by glass, increase bird collisions, Gang says. As a solution, Gang’s team prioritizes using patterned glass near landscaped areas and avoids elements like a glass handrail in front of vegetation.

Undergirded by an ethic Gang calls “actionable idealism,” every Studio Gang project is informed by extensive research and design exploration, which involves no shortage of physical model-making and prototyping. (A significant amount of each office’s square footage is devoted to a bustling workshop.) Whether it’s a community firehouse or a university building, Studio Gang’s architecture responds to the cultural and climatic context of its particular site—sculpted to limit its exposure to direct summer sun or organized to dissolve the line between indoors and outdoors.

Increasingly, Gang is thinking about an Earth-encompassing issue—specifically, how to decarbonize our cities. Currently, Studio Gang is overseeing construction on the University of Chicago’s Center in Paris, a 100,000-square-foot academic hub and student residence with a central, switchbacking stair meant to serve as a vertical “campus quad.” Paris has “much stricter regulations” than the United States, she says, and they take into account embodied carbon, or the carbon emissions required to manufacture and transport building materials. From the very beginning, the project had a fixed carbon budget. “Every material is accounted for,” she says. “We just don’t do anything like that yet in the States.”

Closer to home, a proposal by Studio Gang for carbon-neutral workforce housing in Chicago recently won the C40 Reinventing Cities design competition, which aims to help global cities address the climate crisis. The project, known as Assemble Chicago and located downtown in the heart of Chicago’s Loop, would create more than 200 units of affordable housing atop a wellness clinic and event and meeting space for neighborhood nonprofits.

If built, Assemble Chicago would represent a radical new vision for how to live in the 21st century. Yet its architecture doesn’t dismiss the past. On the contrary, its brick masonry facade interprets elements of Chicago’s historic architecture, namely the bay window, which was invented to bring more natural light into people’s homes. It’s a fitting tribute to the city that launched Gang’s career, a city Gang has now shaped nearly as thoroughly as any architect who came before her.