By Adam H. Graham

Photography by Irwin Wong

I have a place,” my friend Nicola says with a cheeky grin as we walk along Tokyo’s cold, trickling Nakameguro Canal under an inky March twilight. We’d just returned from a ski trip together in Hakuba. Our legs were spaghetti, bones tired, and bellies growling. Fortunately, Nicola, who speaks fluent Japanese and has lived in Tokyo for years, always has a place.

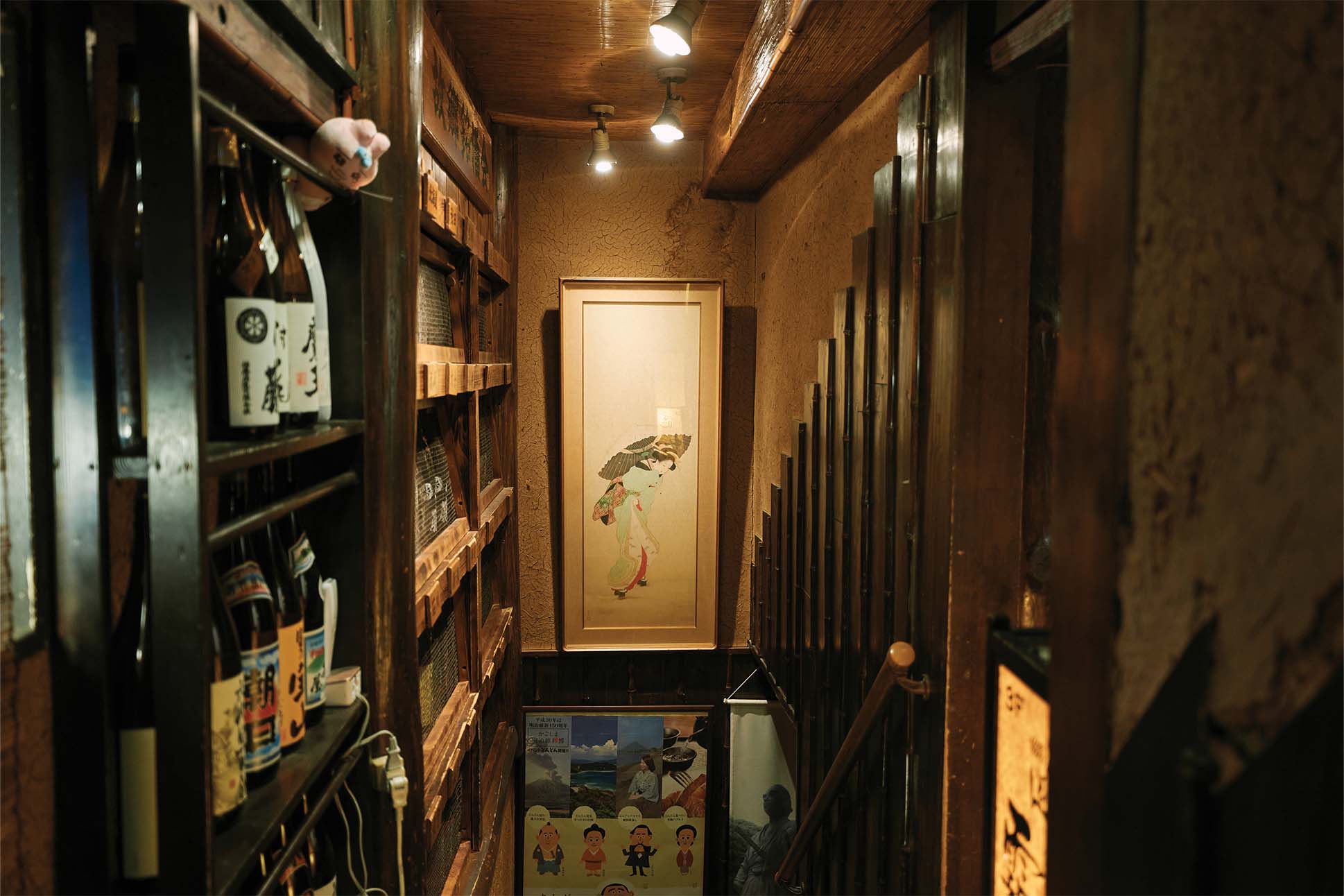

She led us across the canal, past a labyrinth of low-slung neon-lit bars. We passed nabemono (Japanese hot pot) joints, where fragrant steam escaped from sliding shoji screens, and smoky yakiniku (grilled meat) spots, where diners tumbled out laughing, drunk on sake and highballs. “I think it’s here,” she said, crouching down to knock on a Lilliputian door that was half my six-foot-two height. A woman stuck out her head and after a brief exchange in Japanese, access was granted. We crouched down through a padded passageway to enter this secret world.

The joint—Nakame no Teppen Honten—was packed and humming, and we were greeted by a jolly Irasshaimase! Menus in Japanese hiragana and katakana described the seasonal options. A roaring grill behind the counter was a hub of activity, where the izakaya master plated up skewers of grilled shiitake, charred and sliced squid, gooey gratins topped with orange bursts of cod roe, and fluffy tsukune (oblong chicken meatballs on a skewer). Each dish was placed on a long wooden plank by the chef and doled out to diners across the wide bar. It was unlike anything I’d ever seen.

I’d been to many izakayas before, but not until my visit to Nakame no Teppen Honten had I experienced such warmth and conviviality—nor had I realized the lengths to which izakaya chefs go to cook great food in the name of omotenashi, the selfless practice of Japanese hospitality. “How on earth would a non-Japanese-speaking person navigate eating here?” I asked Nicola while we nibbled on crispy karaage and butter-poached scallops, and sipped ice-cold glasses of Asahi. “It’s a good incentive to learn Japanese,” she replied.

Or, they can do as I’ve done—11 years and 20-something visits to Japan later—and streamline the process by learning what I jokingly refer to as “izakaya Japanese.” It may seem daunting to visitors, but armed with a few phrases of Japanese and understanding some basic izakaya rules and etiquette, anyone can unlock the secrets to this truly authentic style of Japanese dining.

The first rule? Ordering a drink. Some izakayas stipulate a one- or two-drink minimum, but teetotallers can opt for soda or alcohol-free beer (ubiquitous because of Japan’s zero-tolerance driving rules). For the uninitiated, izakayas fall somewhere between a pub and a tapas bar. Unlike pubs, which happen to serve food with booze, izakayas emphasize the pairing, making them closer in spirit to tapas bars. Don’t let the casual atmosphere fool you into thinking that the menu is an afterthought.

Most izakayas have a stable of classics you can almost always count on. There are fried dishes: karaage (Japanese fried chicken), croquettes, and crispy soy teba (chicken wings). There are charcoal-grilled skewers, like shiitake and leeks, shiso-ume chicken, and toothsome salted curls of torikawa (chicken skin). Popular vegetable-forward dishes include scored and charred eggplant, asparagus wrapped with thin translucent pork, and blistered shishito peppers. And don’t underestimate the salads—plates of bashed-up cucumbers with sesame oil, cold slices of tomato with a blob of mayonnaise, and tsukemono, seasonal and regional house pickles that are usually a signature of the chef (and often a hint to the prefecture they come from).

It may surprise many that sashimi is an izakaya classic, too. A friend in Kyoto swears that izakayas, not sushi restaurants, have the nation’s best sashimi. After testing his theory across the country, I can’t say he’s wrong. There’s usually a mixed sashimi plate, but to get your first izakaya Japanese badge, say “Osusume no o sashimi wa nanidesu ka?” to the chef to ask which sashimi they recommend. Osusume means recommend, and it can’t be used enough in Japan, where hyper-seasonal local dishes may not always be listed on the menu. When in doubt, nod and say “hai,” which means yes. You’ll seldom be disappointed.

Items you will not typically see at izakayas include sushi, hot pots, kaiseki cuisine, and ramen or other noodle dishes, though I’ve seen all of these at izakayas occasionally, proving that rules are meant to be broken. Children under age 12 are rarely seen. This could be because although Tokyo banned indoor smoking in 2018, many izakayas tolerate smokers, usually on the later side of service after the 7–10 p.m. rush. That may bother many, but for me, a nonsmoker, it’s an “only in Tokyo” throwback I’ve come to enjoy.

Many izakayas accept reservations and, for popular spots, it’s best to book ahead, especially for more than two people. But over the years, I’ve developed a few of my own izakaya routines to avoid reservations and remain spontaneous. I dine on the late side to avoid peak times. And since I’m often alone, I walk around the neighborhood where I’m staying to suss out the vibe at each establishment before committing. I did this one early winter night, still jet-lagged from my overnight flight to Tokyo and not hungry until 9:30 p.m. It paid off when I nabbed the corner counter seat at Yakitori Kadokurasyouten Yoyogi-Hachiman on a quiet Shibuya backstreet near Yoyogi Park.

Another technique I use is to order a test dish before committing to a place. At Kadokurasyouten, I ordered a small sake and a 280 yen ($1.87) plate of hiyayakko, a cold cube of tofu topped with soy, julienned nori, ginger, and scallions. It passed the test, so I got a bigger sake—mori koboshi—poured into a cup that overflows into a wooden retainer (masu), and ordered some grilled chicken skewers and a sublime thin cutlet of pork wrapped around a bundle of chives, called a Chinese chive roll.

Locals are always a great resource for izakaya recommendations. They know the small and out-of-the-way ones, the cheap ones and the pricey ones. One recommendation came from another expat friend living in Tokyo who took me to Iroriya Higashiginzaten in Ginza, a cozy low-slung restaurant with an all-you-can-eat (and drink) option, not uncommon at izakayas. The grilled mackerel and sashimi were excellent; so too the wildly generous servings of ikura, bright orange salmon roe served in such copious portions that it spills over the bowl.

Another favorite izakaya, Shinpo, came to me by a local’s suggestion—and I pay the favor forward to others as often as possible. Shrouded by blue noren curtains, it is known for creamy crab croquettes and iburigakko (smoked daikon slices) topped with cream cheese. Shinpo also serves an excellent version of my all-time-favorite izakaya dish, agedashi dōfu, deep-fried tofu in a savory dashi-based tsuyu sauce, which I often cook at home so I know how tricky it is to perfect.

Shinpo’s was a 10, with its scallion rings and katsuobushi flakes that wriggle from air exposure as if they’re alive.

Even though I’m now fluent in izakaya, I still encounter surprises. One night in the lively Shinjuku while feeling especially worn out and introverted, yet desperately craving izakaya, I discovered the gloriously quiet Oidon Nishishinjuku. I learned about koshitsu, private booths or compartments for one or sometimes two people that shroud the diners behind a sliding screen or a curtain. That night, I slid into my cozy solo booth, ordered a sake, and feasted on lotus root stuffed with karashi (hot mustard), nori rolls piped with spicy mentaiko, and silky grilled stingray fin. Quiet jazz purred in the background. Could I really be in the world’s most densely populated city and experience such tranquility? If ever there was a place to become fluent in izakaya Japanese, this was surely it.