Text by Kathryn Drury Wagner

Quietly yet radically, artist Carl Cheng has been working under the radar for six decades. But that is changing, thanks to the first in-depth museum survey of his art. “Carl Cheng: Nature Never Loses” debuted at the Contemporary Austin, where it will be on exhibit until Dec. 8, 2024. Then it will tour to the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania (Jan. 17 to April 6, 2025); Bonnefanten in the Netherlands (May 9 to Sept. 28, 2025); Museum Tinguely in Switzerland (Dec. 3, 2025, to May 10, 2026); and conclude at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (Sept. 26, 2026, to Feb. 28, 2027).

Alex Klein, head curator and director of curatorial affairs at The Contemporary Austin, spearheaded the exhibition.

“This is a real labor of love,” she says. “We’ve been working on this for four and a half years.” Klein had first discovered Cheng’s work during her time at LACMA, where she became aware of his role in the experimental photography scene of the 1970s in Los Angeles.

In 2020, she invited Cheng to do a survey. They met remotely for two hours, every Monday, for two years. “We went project by project, year by year, through his work,” she says. “I had an amazing curatorial fellow who helped me create a big taxonomic structure for his work. This is an artist who never really had consistent gallery or institutional support. So, we had to go back and do that archival process.” Her work included documenting his past public and installation work, pieces that have not been seen since they were originally presented.

Ninety percent of the sixty-plus objects in Nature Never Loses came directly out of Cheng’s studio in Southern California. Curation was challenging, Klein notes. Cheng often creates kinetic work that moves or makes sound, and frequently chooses unconventional and organic materials such as avocados. Some of his art is ephemeral and made to disappear.

Some such works were restored, such as “Sand Rake Art Tool”, from 1978, that creates a site-specific, large-scale sand drawing. “There are so many other works that still need to be restored,” Klein says. “Carl is 82. He’s got a lot left in him to give. I am hoping that, while there is still time, some of these other important artworks can be restored and that this show will provide visibility toward that.”

Cheng, she says, “is an artist that defies categorization. I often describe more the thematic aspects of his work, looking at the intersections of identity, technology, and ecology. He’s very responsive to the times he is in, and to new materials and tools–to new ways of making artwork.”

His sculpture series “Erosion Machines” encapsulates many of the aspects of Cheng’s work. In creating it, he experimented with ideas of erosion, and how humans both alter and are altered by the environment. With the effects of climate change escalating, his art takes on a new sense of urgency.

Cheng has a dual background in industrial design and art, which informs his perspective, says Klein. “He was also heavily influenced by Marcel Duchamp. And he traveled extensively in Asia and Southeast Asia in the early 1970s, which liberated his ideas of where art needed to be located, what it needed to be made of, and how it could be made. So, he’s within certain trajectories of non-Western art practices, looking at those ideas that art doesn’t have to be bought and sold, that it can fade away or erode. He wouldn’t want to lay claim to those ideas but they get incorporated into his practice.”

As part of his artistic practice, starting in 1967 Cheng created an alternate identity, an anonymous entity called “John Doe Co.” It can be seen, for example, in his 1972 work “Art Tool Paint Experiments (Paint Dipper in Display Box).” John Doe Co. reflects Cheng’s humble and modest personality, his concerns about corporate culture and the Vietnam War, and his experiences as an Asian American.

“He is both prescient and completely of the moment,” says Klein, noting that Cheng explored concepts of the Anthropocene before there was even a term for that.

“Alternative TV #3,” 1974. Plastic chassis, acrylic water tank, air pump, led lighting and controller, electrical cord, aquarium hardware, conglomerated rocks, and plastic plants courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles. Image by Ruben Diaz.

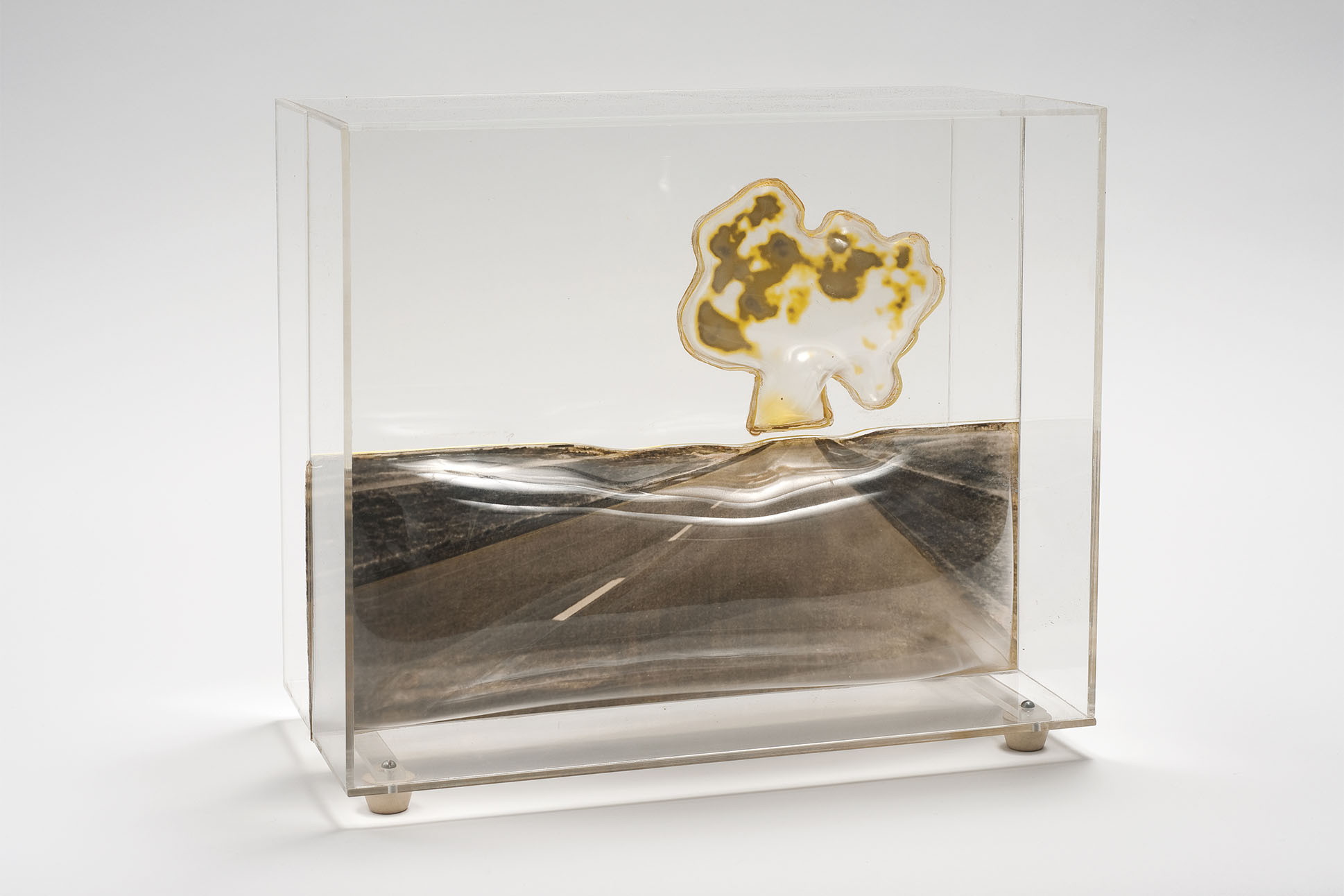

“Nowhere Road,” 1967. Film, molded plastic, and plexiglas collection of Beth Rudin Dewoody, Los Angeles. Image by Robert Wedemeyer.

“Early Warning System,” 1967-2024. Fabricated plastic, electronics, projector, wheat, wooden base, and radio tuned to local weather station. Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Purchase, by exchange, through a gift of Michael D. Abrams.

“He’s a Californian; he’s grown up watching the farmland turn into suburban wasteland. He’s using the same lacquer paints as the Finish Fetish artists are using. He’s asking different questions of land art than the land artists but he’s contemporaneous to many of them. He’s working alongside other artists but coming to a different conclusion.”

Klein says she hopes that art audiences leave the exhibition feeling the generosity in Cheng’s work.

“His art inspires the viewer to think outside the box,” she says. “What if our technology was organic and biomorphic, instead of computer chips and rigidity? What if we rethought our foundational technologies and approaches to the environment?”

Cheng, she notes, has influenced many younger artists—even if they weren’t fully aware. “There are people who are inheritors of his practice,” she says. Examples include Jes Fan, who works with organic materials and unstable materials, and Josh Kline, whose recent show at MOCA featured melting ice to comment on climate change.

“I think he’s an unacknowledged predecessor that I am very excited for people to discover,” she says. “He’s not an easily identifiable artist but such an important linchpin for a lot of the pressing concerns of our moment and the way artists are working today.”