Text by Julia Eskins

Images courtesy of Bata Shoe Museum

Walk down Toronto’s Bloor St. Culture Corridor, and you’ll likely notice a unique building shaped like a shoe box. Clad with French limestone resembling the texture of leather, the Bata Shoe Museum houses the world’s most comprehensive collection of footwear—nearly 15,000 shoes and related artifacts spanning 4,500 years of history. From a 16th-century Italian velvet mule to Elvis Presley’s blue and white patent loafers, every object tells a story. With permanent and rotating exhibits, the museum explores how culture, history, politics, nature, and people have shaped that narrative.

The treasure trove of shoes was born out of the personal collection of Sonja Bata, who began traveling in the late 1940s with her husband, Thomas, of the shoe manufacturing and retail business Bata Shoe Company. Fascinated by traditional footwear, she started accumulating examples, soon amassing one of the largest holdings of moccasins in the world. To maintain the artifacts and fund field research, she established the Bata Shoe Museum Foundation in 1979. After more than a decade of searching for the right location, the Bata Shoe Museum opened in 1995 on Bloor Steet, steps away from Toronto’s high-end shopping district and other cultural institutions like the Royal Ontario Museum.

At the time, fashion wasn’t taken seriously in the world of academia—Sonja Bata helped bridge that gap. “She was not somebody who simply wanted to look at shoes and think of them in terms of their beauty and their construction,” says Elizabeth Semmelhack, director and senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum. “She saw shoes as an entry point into larger cultural ideas.”

A collection this vast needed an equally inspiring home, which is why Bata enlisted acclaimed Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama to design the building. Inspired by the boxes that protect shoes from light, dust, and moisture, Moriyama conceptualized a container-like building with a copper “lid” and a wedge-shaped glass entrance. The award-winning three-story structure welcomes visitors with a light-filled atrium and a cantilever glass-and-steel staircase that leads to the exhibition spaces and conservation facilities. Nods to the artisanal craftsmanship—leather signage and cast bronze medallions depicting shoes—are integrated into the space. Downstairs, subterranean vaults store the collection. Only three to four percent of it is on view at any given time.

Many of the artifacts in the permanent collection, which unfolds in the lower level, were among Bata’s favorites. The journey starts with some early examples of footwear: 6th-century sandals from ancient Egypt; 13th-century socks made by the Ancestral Puebloans; and ornate silver mules from 19th-century India. As guests wind through time, they can also view shoes worn by celebrities, such as Queen Victoria’s ballroom slippers, Robert Redford’s cowboy boots, and Elton John’s monogrammed silver platforms.

Since Bata’s passing in 2018, the curatorial team has continued her legacy of collecting, conserving, and studying these items through different lenses. In April 2024, the museum opened “Exhibit A: Investigating Crime and Footwear,” which explores a range of issues from social biases related to fashion and reflected in how people are policed to footwear forensics. The exhibit starts with a pair of butler shoes—a nod to the typical “whodunit,” in which the silent and overworked butler is often the prime suspect—and concludes with a look at the Kingston Penitentiary, which taught prisoners shoemaking as a reform tactic. (The exhibit will be on display until fall of 2025.)

When it comes to fashion, people often consider the designer or the wearer, but there are endless opportunities to tease out stories about all the hands that went into making a pair of shoes, says Semmelhack, who co-curated the exhibit.

When including indigenous footwear in an exhibit, the museum takes a “nothing about us without us” approach, adds Semmelhack. For example, with “In Bloom,” an exhibit focusing on plant motifs and materials, the team collaborated with three indigenous guest curators who shared their expertise on a set of floral moccasins. (“In Bloom” is on exhibit until October 2024.)

The museum is also sensitive about provenance when adding to its collection, she says. Historical items are often donated by families. And with future exhibits in mind, the team acquires noteworthy contemporary pieces like the New York art collective MSCHF’s Big Red Boots, which took the internet by storm in 2023.

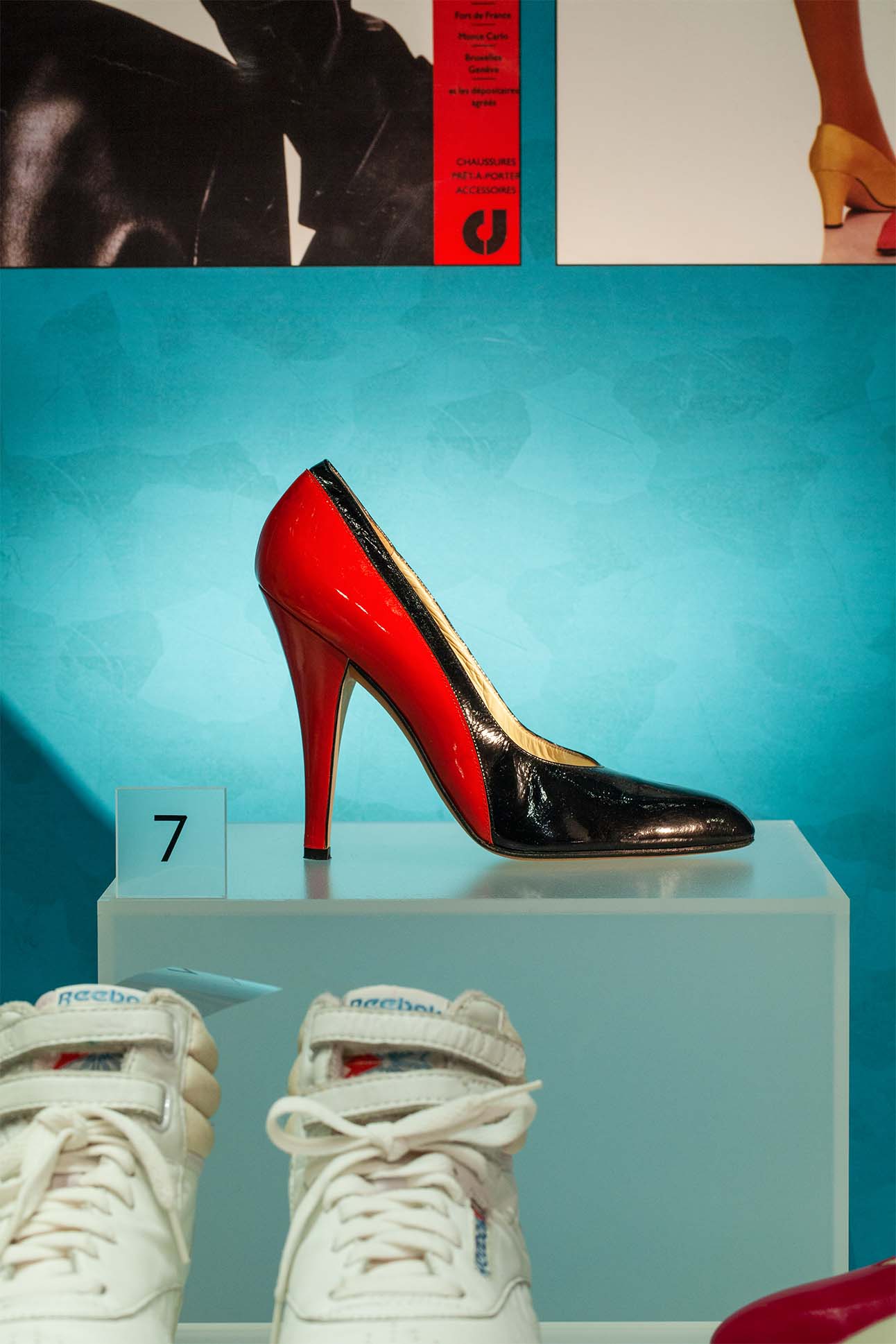

After noticing the collection’s deficit of 1980s footwear and the decade’s recent revival in pop culture, Nishi Bassi, curator and manager of exhibitions, came up with the idea “Dressed to Impress: Footwear & Consumerism in the 1980s,” now on exhibit until March 2025.

The exhibit explores how popular trends like the oxfords worn on Wall Street, the “Silicon Valley Uniform,” and low-heeled shoes made popular by Princess Diana reflected an atmosphere of conservative politics, globalization, and technological innovation. The exhibition space, designed by Toronto-based Arc & Co. Design Collective, feels like stepping into a mall from the era of excess, with white tiles, artificial plants, and retro display cases.

“It strikes a really good balance between some serious probing questions about culture and consumerism and a very nostalgic look at a period where conspicuous consumption was all the rage,” says Bassi. “We still love to create very immersive spaces, whereas a lot of other institutions are moving more toward a more minimalist design.”

That immersion extends to the museum’s programming, including live panel discussions, performances, shoe design workshops, and free admission on Sundays. Upstairs, a conservation lab offers visitors a behind-the-scenes peek at the process of restoring footwear artifacts. And on the lower level, family-friendly crafts engage a fresh generation of footwear fanatics. Thanks to Bata, the world’s most special shoes have a home inside a dazzling stone shoebox—and a growing audience to step into their stories.