By Scott Bay

Ceramics are often the result of form versus function. Should pottery be strictly utilitarian? Or should everyday objects serve a purpose while being visually pleasing? Opinions on the matter are strong and lasting. The art form dates back at least 28,000 years, with different eras and cultures shaping their particular needs from the clay. Some created figurines for rituals or as symbols of fertility, while others introduced products like vases, bricks, and tiles for the built world. The reality is that the answer falls somewhere in between. Found in the unknown.

That unknown excites these five ceramicists, who are pushing the art form forward in inventive and playful ways. Each chose clay as their medium, in part, because it’s impossible to completely control what happens within the kiln; the element of surprise creates a collaboration between the artist and the material.

This dance has become a practice for creating personal works: delicate, paper-thin, large-scale objects that are deceptively lightweight, shapes that reflect the natural landscape, blooms that balance the masculine and feminine, and social justice messages on classical porcelain vases. The process of firing clay, made by hand and heart, is still providing new shapes, materials, glazes, and, of course, both form and function—30,000 years later.

Mesut Öztürk

After practicing architecture for three years in his native Istanbul, Öztürk craved something more pliable with which he could create. He turned to clay. “I approach ceramics as a way to entertain myself, experimenting freely,” he says. “When I create something that resonates with me, it becomes an artwork. It isn’t about grand narratives or deep meanings—I explore how forms make us feel, how they interact with space, and how they exist on their own terms.”

Öztürk’s work explores the timeless nature of clay—which can be millions of years old—being shaped anew, by playing with eternality and how ceramics, especially with Türkiye’s rich cultural heritage, embody that sense of permanence. He opts not to use glazes, rather coloring his works with paints while keeping the surface rough. “Many people don’t like the idea of a table without a waterproof surface, but I like contradictions,” he says.

Since he began his ceramics journey in 2018, the art world has embraced his organic forms with exhibitions in Paris, Brussels, Basel, Milan, Rotterdam, and Cape Town. “I am consistently fascinated by how the material can carry history yet remain contemporary,” he says.

Chloe Park

The Los Angeles-based artist is fascinated with juxtapositions—namely, the masculine and feminine. She thinks both can be beautiful and appear however they want, such as with clay, a heavy material, formed into a delicate flower or a soft ruffle inspired by a gown grazing the floor. “I want to bring the masculine harshness of the material with a very feminine intention and form,” she says.

But she also applies her value system and spirituality to her artistic practice. “Ruffles, for example, not only embody the beauty of fabric,” she says, “but they also reveal the hidden and unspoken—the never-ending tapestry and the fabric of being.”

Park is a student of life. She often references her influences—Martin Luther King Jr., Ram Dass, Quincy Jones, and Miuccia Prada, to name a few—all part of a mission to be ready for inspiration. “I find, for me, at the root of it, is devotion and discipline,” she says. ”The love drives the work ethic and the work ethic carries the inspiration to create the work.”

Park saw artist and architect Gaetano Pesce speak before he passed away last year, which became a pivotal moment for her process. “He said beauty opens people up, and it’s so true, because ugliness in the world can shut us down,” Park says. “I want people who see my art to remember the beauty of opening. In a world where we’re constantly being pulled to close, I want them to open, open, open.”

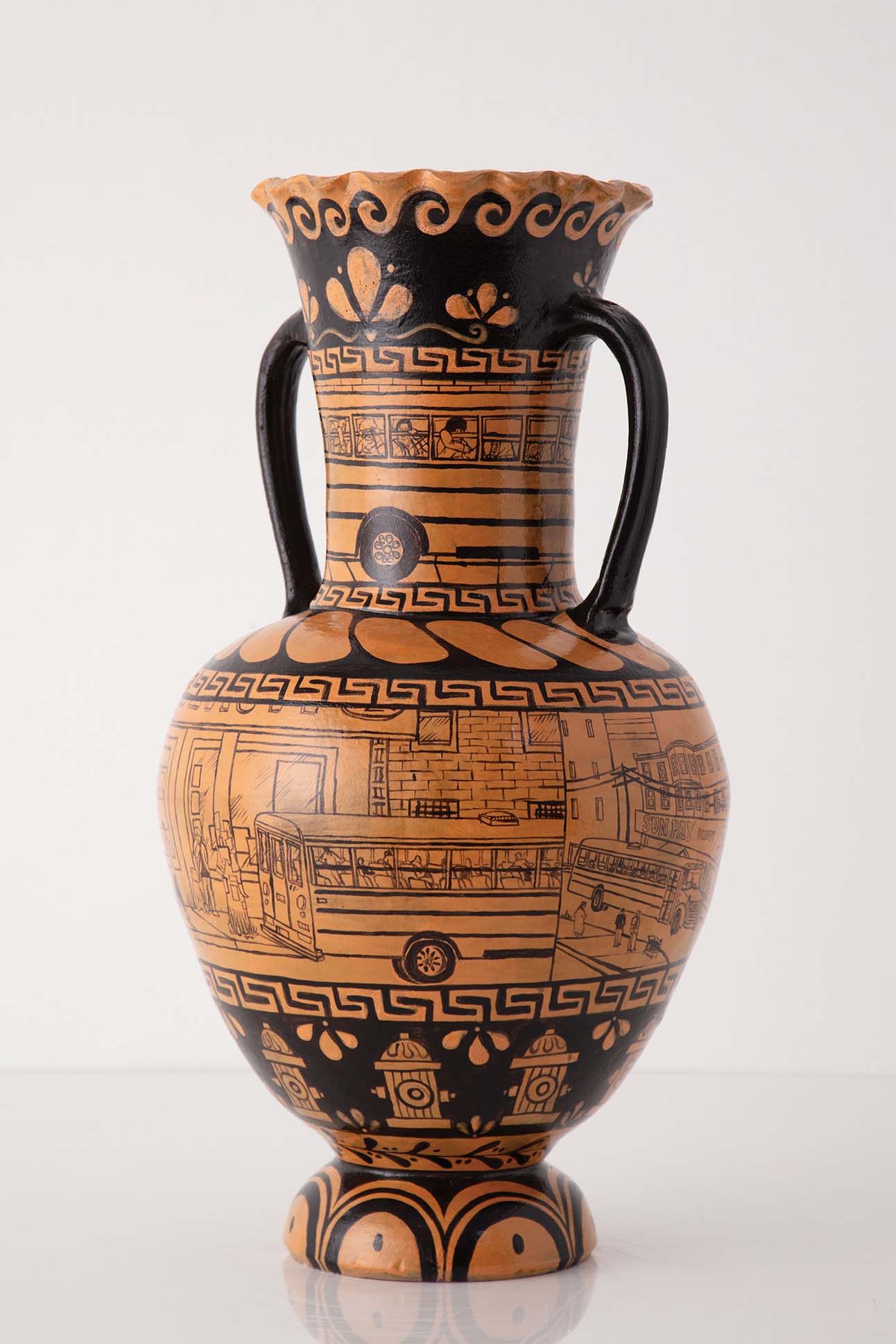

Roberto Lugo

Revered for ceramics that subvert the traditional, Lugo uses familiar classical forms and reimagines them with a 21st-century lens, inspired by urban graffiti and hip-hop culture. His deeply personal work speaks directly to his Puerto Rican heritage and upbringing in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia.

“I find that the representation that I have in my work, and displaying it in places like museums, is serving the community that I come from,” he says. “A lot of the time, people finally feel seen in that sort of context.”

He finds importance in being an artist who knows what he is trying to say with his work. His process: “I will start by throwing pottery in recognizable classical forms, then I research what’s going on in the world, in terms of current events, and I often use my work as an opportunity to speak to those issues.”

Lugo is also an art education activist for impoverished communities in the United States. Occasionally, he sets up a pottery wheel with the label “This machine kills hate,” on the streets of Philadelphia and gives free lessons to local youth. His goal is to inspire his community to pursue the arts, which he believes will create a better world. “The idea of being able to kill hate is just another way of saying that this machine is limitless,” he says. “It has the potential to do really great things.”

Natalie Paolinelli

Heavily influenced by the Pacific Northwest, Paolinelli wondered whether she could create what she was seeing as a creative and technical challenge.

“When I first started making ceramics, it was a bunch of mix/match, playing with the material and seeing what it could be,” she says. “But I think maybe a year or two into the process, I started seeing forms around the coastline and in the forests, and thinking, I wonder if I could do that with ceramics.”

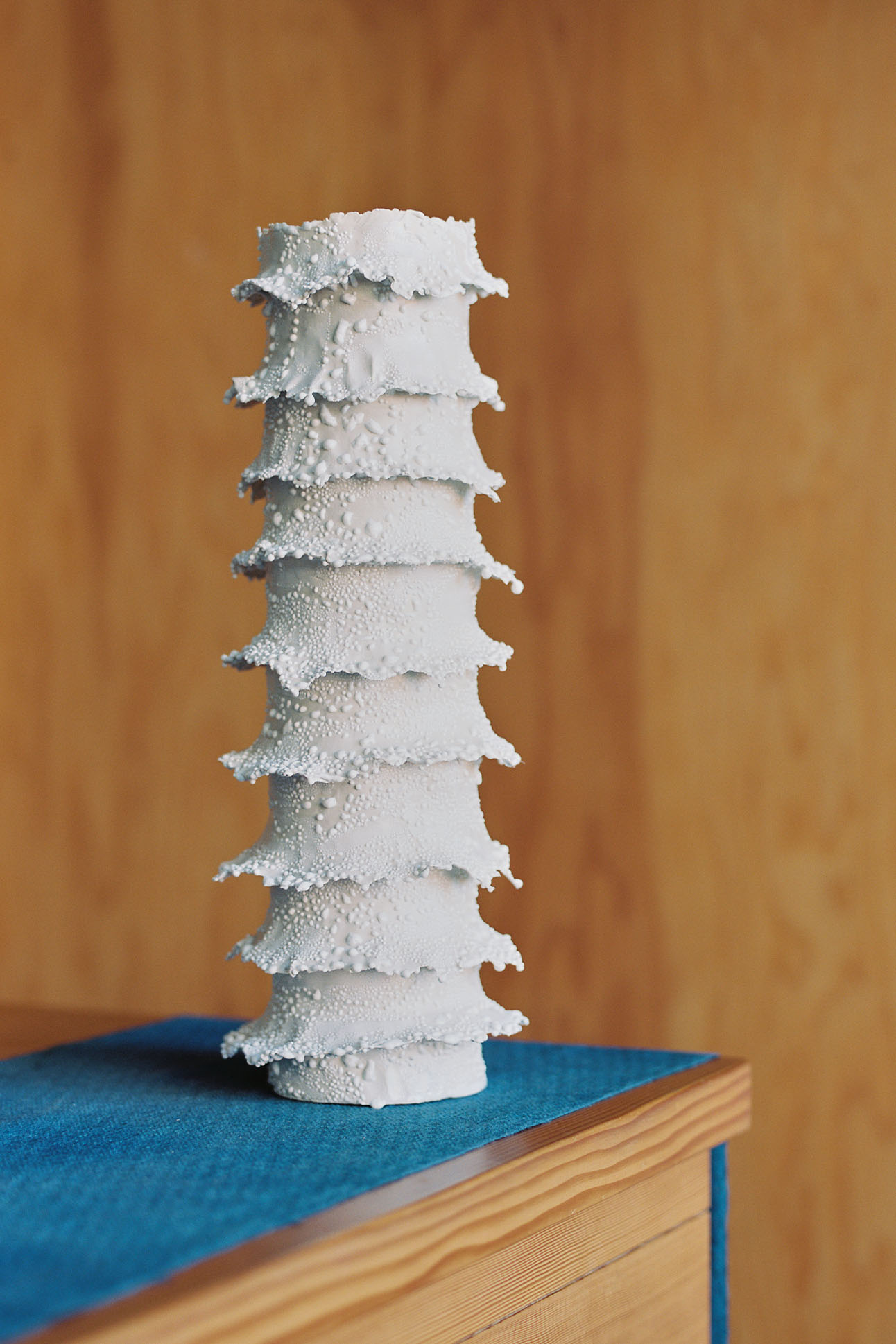

Today, Paolinellli applies novel glazes onto organically shaped pieces in a Vancouver studio located in a pink barn. While her work reflects living objects, such as coral, barnacles, trees, and kelp, she always leaves room for the process to show her the way. “There is this unpredictability when it’s in the kiln,” she says. “You have no control, and you think, ‘I hope it works.’ I love that.”

Paolinelli does not sketch—she forms. “There is only so much time before it dries. My house is like a graveyard of my experiments, where every work that sort of maybe might be an idea is archived,” she says. “The idea might be too wild for the world to see yet, so I just keep forming clay, because I get so much from it, and I feel like it’s part of my existence.”

Paola Paronetto

When Paronetto began her career 40 years ago, she found inspiration in nature and wanted to craft objects that showcased the way the natural world makes her feel: peaceful, light, and calm. For the Italy-based artist, traditional clay was not strong enough to provide the thinness she desired. That’s when she discovered paper clay, a mixture that uses paper pulp and reduces the chance of breakage when fired. It allows for extravagant and extreme forms that are incredibly lightweight.

“The world is moving so fast and everybody nowadays is in competition, which kills originality and diversity,” she says. This is challenging for Paronetto, who values creativity and seeks to lead a slow lifestyle, which she says leads to flashes of inspiration. Her studio in the small northern region of Pordenone employs all women with whom she shares her ethos and proprietary knowledge of earth and water.

Her work uses matte colors that, after being fired three times at specific temperatures, produce a velvety texture that “inspires a moment of pause,” she says. Paronetto hopes her work encourages her patrons to follow in her footsteps, desiring a slower pace and spending more time in nature and with family. “With time, I have learned that this job was a research in myself, more than anything, and I can now see myself in the pieces, which brings me joy.”