Text by Eunica Escalante

Images by Kevin Scott

As a child, David Montalba’s favorite pastime was rearranging his bedroom. He thrilled at the seemingly endless configurations of furniture, the latent potential of unlocking the novel in a room that just before felt stale in its familiarity: changing the orientation of the bed to open up the space or moving the desk from the shadowy entryway to face the windows instead, so that natural light can spill unencumbered onto its surface.

Growing up, I too enjoyed the act of transforming my childhood bedroom. After all, commanding sovereignty over one’s personal space is a natural symptom of coming of age; an expression of one’s fledgling independence.

For Montalba, though, the act transcended that typical adolescent itch for autonomy. Because even from a young age, he knew a room wasn’t just a room. That the spaces we inhabit are more than places to eat or sleep or congregate. Our relationship to our built environment isn’t unilateral, it’s reciprocal: as we change our surroundings, so too do our surroundings change us.

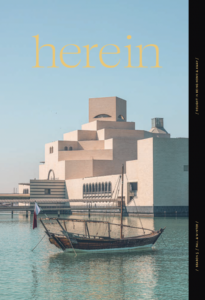

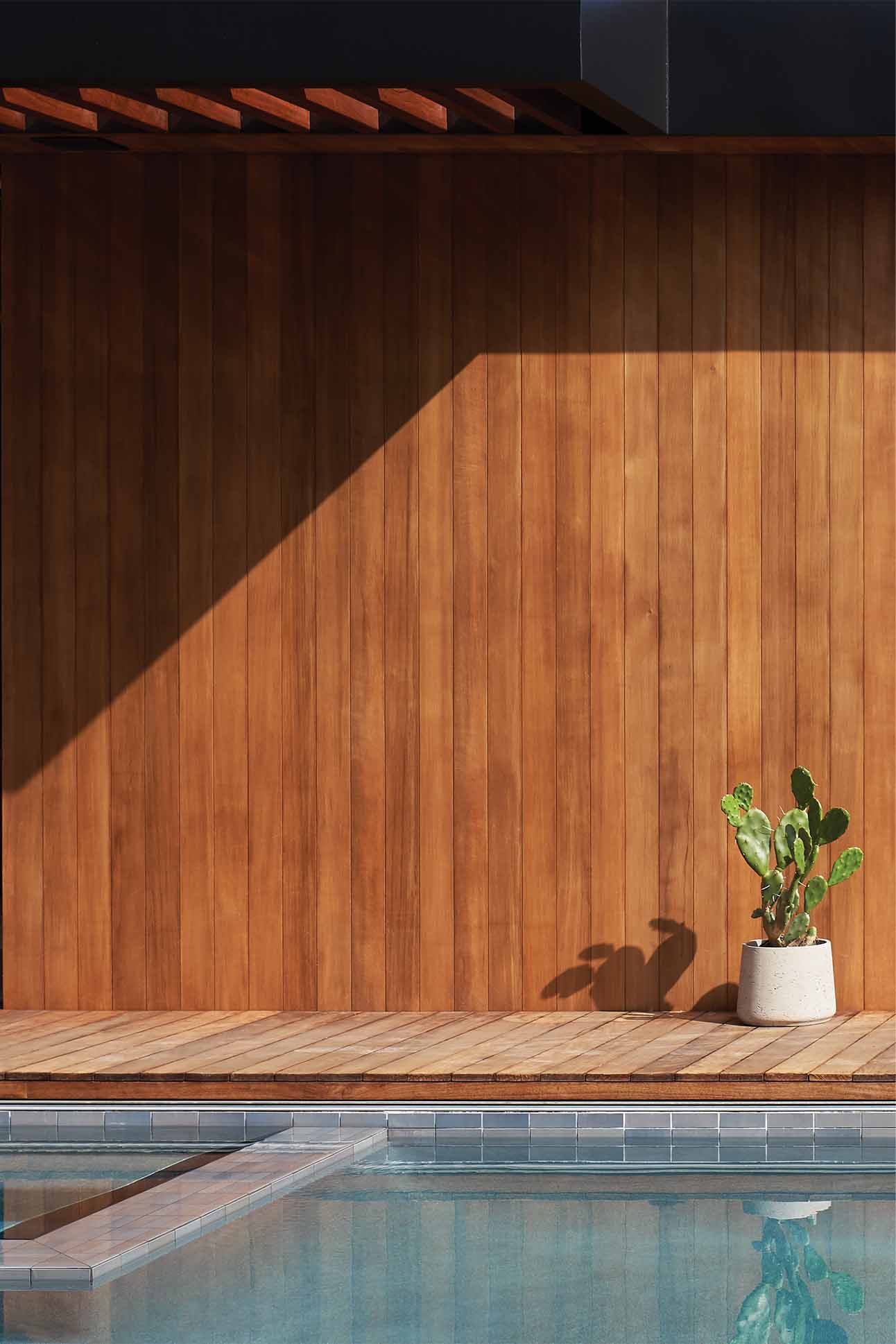

Montalba Architects Venice Beach house in Venice, California.

“Something as silly as reorganizing the furniture in my room when I was 10 years old and realizing how much that affected me emotionally—that quickly gave me an awareness of the power of design,” says Montalba, from Santa Monica, where he currently lives and works. In true Los Angeles fashion, he dials into our virtual meeting from his car as he drives from one appointment to the next. It’s symbolic of that famous facet of L.A., its residents’ so used to life on the go.

And yet, it’s also indicative of the cadence of Montalba’s own life. As the founding principal of the award-winning firm Montalba Architects, he is undoubtedly always in demand. His daily itinerary is filled with business meetings and client consultations, not to mention helping to oversee the numerous multidisciplinary projects his firm handles. Theirs is a portfolio that encompasses breathtaking residential homes and mindful office spaces, sleek airport terminals and immersive resort properties—spanning the urban streets of New York and Los Angeles to the bucolic landscapes of Switzerland and Wyoming.

He founded Montalba Architects in 2004, a firm rooted in a design philosophy that Montalba describes as a humanistic approach to architecture. “Ultimately, we’re designing a building or a space that’s really focused on how one experiences it,” he says. “Whether it’s crafting a large-scale building that acts as a public space or a home, it’s really about trying to craft and improve the day-to-day experience.”

It’s a philosophy Montalba traces back to those childhood days rearranging his bedroom, influencing his formative understanding of design’s visceral effects. For the past 27 years as an architect, many of which include his career as a principal founder of his own company, he has honed this humanistic approach into an ideology of thoughtful design. “We bring an experience-focused and humanistic approach to all aspects of the architect process,” Montalba has said in the past. “We focus on how we experience space and how the building will affect our lives.”

One can see this ideology manifest across Montalba Architects’ dossier of projects, which features works for the likes of Sony Music, The Row, and his own home. Though the firm has cultivated a signature style over the years—exemplified by pared down aesthetics in favor of elegant functionality and a championing of material integrity—no two buildings ever look or feel the same. Each one is alive with its own character, its personality manifesting in its carefully curated materials or its distinctive expressions of technique.

This structural sui generis is a result of the firm’s approach to design, wherein a building’s context—its location, history, and landscape—is among the primary drivers of its look, feel, and flow. “You have to be contextual and really think about your surroundings,” Montalba explains. “For us, being thoughtful participants in the built environment, knowing what is around us and really responding to it, that is really important.”

Take the Headspace Santa Monica Campus as an example. When the popular meditation app’s success led to quickly outgrowing their original offices, the company turned to Montalba Architects to design a spacious multipurpose headquarters. It would be located in Bergamot Station, the nearly 5-acre swath in eastern Santa Monica that over the years has transformed from its original industrial roots, historically home to railroad stations and factories, to what is today a sprawling artistic complex.

Working within the context of Bergamot Station’s distinctive history, Montalba Architects chose to preserve two of the site’s existing steel structures, lending the headquarters’ buildings an industrialized feel. Materials like the corrugated metal exterior and concrete floors, and design choices like an exposed truss ceiling and the bi-fold garage door opening onto a sprawling courtyard, converted from an erstwhile parking lot, served to heighten the aesthetic. Repurposing the extant buildings wasn’t just for appearances, though. It meant a spacious floor plan, purposely kept open by the firm’s design team to facilitate the organic ebb and flow of productivity and communion—a key tenet of Headspace’s company values.

In contrast, Montalba’s own family home, dubbed the Vertical Courtyard House, takes inspiration from a surrounding neighborhood of single-family residential homes. Hoping to blend seamlessly with their Santa Monica Canyon neighbors, Montalba chose to limit the property’s vertical footprint. “We were allowed to build a taller home,” he says. “We intentionally built it smaller because we wanted to fit into the neighborhood.”

Whereas others would have turned to the surrounding environment for views of natural landscapes, Montalba chose to look inward. The house’s nickname is drawn from its three-story courtyard and atrium, ensconced at the heart of the property. In centering the courtyard, the home’s design blurs the divide between the internal and the outdoors. Expansive, operable glass walls eliminate the traditional physical and visual barriers, and the home’s interior spaces become a natural extension of the greenspace beyond. “Every outdoor space in that property is an extension of the indoors—that was really intentional,” Montalba says. Beyond inviting the outdoors in, the fluidity of its boundaries delivers ample natural light and air into the space, making its rooms and corridors feel even more expansive. A Japanese Zen aesthetic brings a certain tranquility onto the space, compared to the innovative energy felt within Headspace SM’s industrial walls.

“They’re a little like children, right?” Montalba says, explaining the firm’s contextual approach. “You can’t force a personality on your children. Yes, you can influence them a little, but at the end you have to listen to them. For us, projects are about listening to the client and the site conditions. Sure, we want to guide that, but ultimately it needs to reflect a little bit of the client’s personality and the site’s personality.”

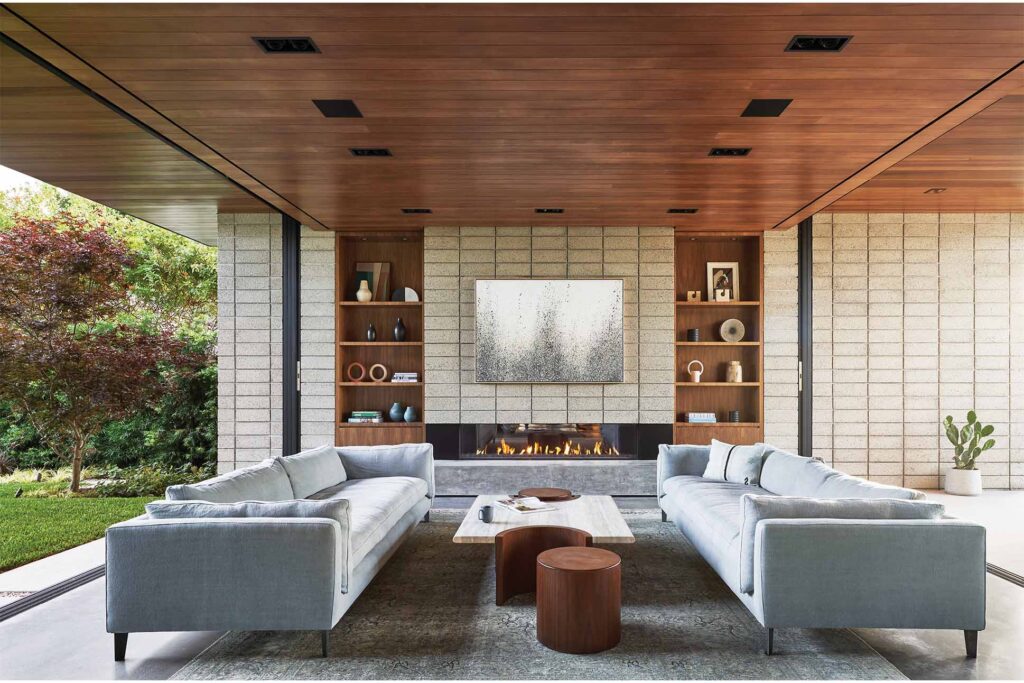

Full height sliding glass doors open the main living space to the exterior at Venice Beach house.