By Scott Bay

On the edge of a glacial lake in northern Idaho, the entire facade of a house called Dragonfly seems to disappear. A massive guillotine-style door—framed in steel and glass—seamlessly slides with the crank of a wheel, completely transforming a sealed room into a breezy living room between nature and home. It is a distillation of Olson Kundig’s philosophy: Architecture is not fixed, but an active participant in the lives of its inhabitants.

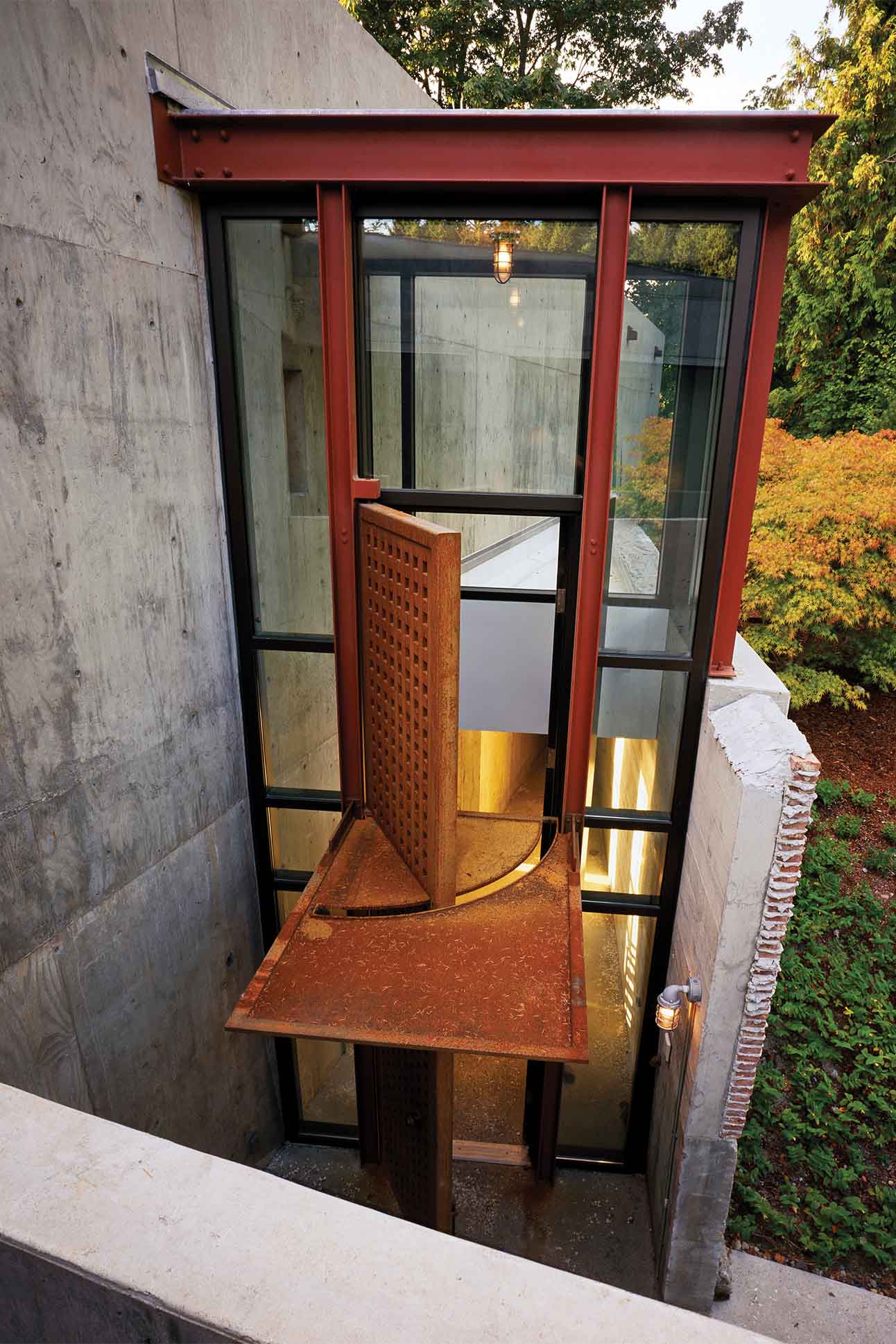

“When you touch a building, that’s your handshake with it,” says Tom Kundig, principal, owner, and founder of the Seattle-based architecture firm known for spaces that quite literally move. “You’re becoming part of the device. It is you who turns the wheel or lifts the wall, and suddenly, you’re more connected to that place than you were five seconds ago.”

Jim Olson, the other half of the firm’s founding duo, adds, “The world is in constant motion. No two minutes are ever the same. It’s about humans adapting to the changing world around us. Like dandelions in nature closing at dusk and opening back up at dawn, architecture becomes a vessel to adapt to all the cycles of life.”

Dragonfly is just one example of the firm’s kinetic projects: a portfolio defined not by flashy interventions, but by designs that move with purpose—pivoting panels, crank-operated windows, and drawbridge-style doors that shift the character of a space in real time.

The new short film Counterweight traces that lineage from early experiments to real-world execution, while a November-released Phaidon monograph, Tom Kundig: Complete Houses, offers a tactile blueprint of the architect’s ideas developed and refined over four decades.

Like dandelions in nature closing at dusk and opening back up at dawn, architecture becomes a vessel to adapt to all the cycles of life.

—Jim Olson

Kundig describes his earliest influences as mechanical. “I grew up around extraction industries—logging, mining, and agriculture,” he says. Watching huge machines move with elegance and purpose fascinated him, and later, working with artist Harold Balazs on his abstract metal sculptures, he saw how pulleys and sandbags could animate sculptures. “These basic engineering solutions inspired me to move large-scale things, much bigger than us, within architecture.”

This tug and pull is evident in Maxon Studio, a steel-clad office designed to slide along railroad tracks through a Washington forest clearing. “Our client Lou Maxon approached us with an idea of designing a home office he could commute to,” Kundig says.

“We joked about deploying Lou into the forest, and from there we developed the idea of putting the studio on railroad tracks so the office could move across the site.” What began as a jest evolved into a structure that embodies both whimsy and functionality.

For Olson, movement is not only mechanical but experiential. “Creating architecture is like choreographing a dance,” he says. “You’re figuring out how to move from one space to another.” He also likens it to Japanese gardens, where “even the smallest details become a special moment that you discover as you walk through.”

This ethos often manifests in designs that dissolve the barriers between the built and natural world. “I’ve always been a very context-driven designer, and I think it’s important not to compete with the landscape,” Kundig says. “If you start with the primacy of the site, everything else becomes a direct response to that particular place.”

The firm’s JW Marriott Los Cabos demonstrates this approach at scale. The desert landscape comes right up to the building, which consists of sand-colored stone and stucco, echoing the beach steps away, while also dissolving into the surrounding terrain. Meanwhile, in Seattle, the firm’s intervention at St. Mark’s Cathedral uses their skill set for performance.

“The glass doors are an experiment in creating motion within a spiritual space,” Olson says. “You hear music behind the screen, and as it opens, the choir is revealed. It is dramatic.”

What makes these gestures even more compelling is their analog quality. In an era of digital automation, the duo insists on utilizing manual mechanics. Kundig sees this tactility as essential. “When a user takes hold of a wheel and turns it, the effect is not only physical, but emotional,” he says. “You’re the motor. It makes you think more deeply about how you take up space, which in turn promotes a sense of stewardship for that space.” In the end, each wall that rises or threshold that shifts reminds us that buildings—like the people who inhabit them—are meant to move with the patterns of nature.