Written and Photographed By Jennoa Matthes

Under a cloudless blue sky, the climb to Lefkara is a slow unraveling of Cyprus’s interior: fields gone golden, olive branches swaying in dry air, and the scent of dust and forest pines rising from the roadside. It’s early June, but the sun has already taken hold.

The narrow streets are quiet when I arrive, save for the gentle chatter of shopkeepers, preparing for the afternoon rush. I peruse storefronts selling local crafts, including L. Papaloizou–Cardiff Lefkara Lace Workshop & Silver, a generational family business whose owner’s great-grandmother was the first to take Lefkara lace abroad, and Lefkara Arts and Crafts, which works with a small group of women who embroider lace for their shop.

When I step into Rouvis Lace and Silver, where Michael and Toula Rouvis and their son, Demos—a family of lace makers—carefully carry on Lefkara’s most celebrated tradition, I’m greeted like an old friend. I’m handed a glass of freshly squeezed lemonade and given a tour.

Shelves are piled with folded lace, some recently completed, some vintage, and even a few pink pieces that Demos noted with a grin were “very popular in the ‘80s.” Upstairs, in their family home above the shop, he shows me his mother’s dowry: a finely embroidered white tablecloth that they still use for family celebrations.

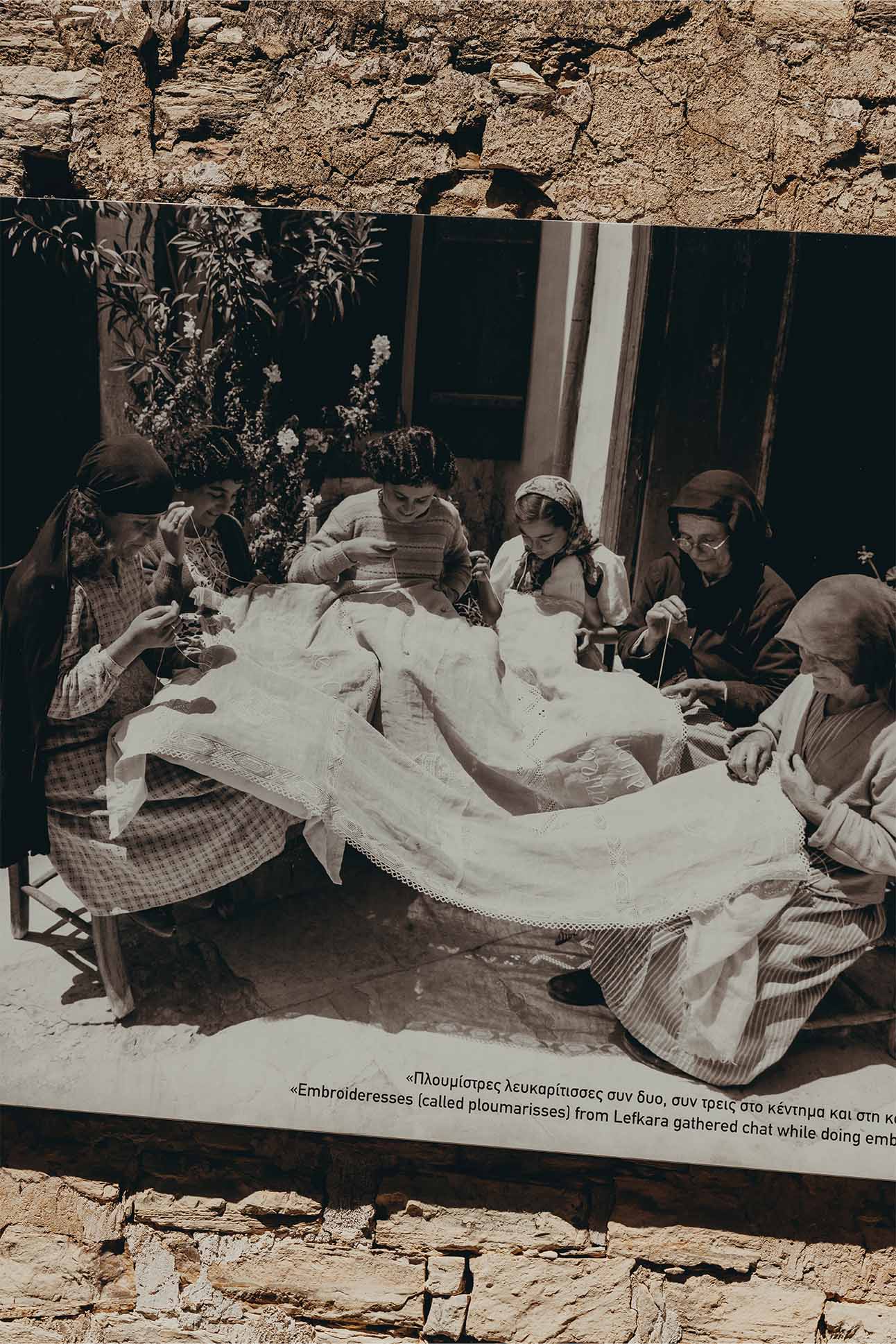

Over the centuries, Cyprus passed through the hands of Byzantines, Venetians, and Ottomans—each empire leaving its mark, especially visible in the architecture of Lefkara. During Venetian rule in the 15th and 16th centuries, this small village became a favored summer retreat for nobles, who helped transform the handiwork of local craftswomen into a now-iconic style known as lefkaritika, or Lefkara lace.

This uniquely Cypriot art form was officially recognized by UNESCO in 2009 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The village sits between Larnaca and Limassol, two of Cyprus’s largest cities, and is considered one of the most beautiful on the island. Among the handful of narrow streets that run through the village are still craftswomen, needle in hand, quietly stitching among artisanal shops.

One of the first things that catches my eye is a large print of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper hanging on the wall.

When I ask Demos about it, a conspiratorial smile spreads across his face. According to local legend, da Vinci visited Cyprus in 1481, during Venetian rule, and the artist brought a piece of Lefkara lace back to Milan with him. Later, similar geometric motifs appeared in the tablecloth on his famous painting.

Whether fact or fable, the tradition clearly made an impression: In 1986, a Lefkara tablecloth was commissioned for the altar of Milan’s Duomo for the 600-year anniversary of the cathedral’s foundation. It was designed by Demos’s father, Michael, and hand-stitched by three Lefkaran women over seven months—a tight deadline for a project that would normally take two years. Demos points with pride to a framed photo. “My father delivered it on the exact day it was due,” he says. “October 19, 1986.”

Toula, who learned the craft from her mother and grandmother, shows us a piece she has been working on. “Each design begins with stiff Irish or Belgian linen,” she says, carefully counting the stitches and marking the layout by hand. “Everything is done from memory. No two pieces are the same.”

What began as a way to decorate their homes evolved into a source of economic independence for women in the village for over a century. These days, the art form is kept alive by a devoted few. “There may be only 40 women left who know how to make it,” Demos says. “The youngest is 60.” Most are in their eighties.

With fewer artisans earning their living through Lefkara lace, some are working tirelessly to preserve the tradition. A few schools still teach the technique, and hobbyists are seeking out the intricate knowledge.

Demos understands that the future of the craft is uncertain, but he speaks with quiet resolve. “My father has been doing this his whole life,” he says. “It’s a true passion. As long as we can keep doing it, we will.”

Lefkara and Beyond

Eat Like a Local

HOUSE 1923 Tavern is a go-to for traditional Cypriot dishes—try the chicken souvlaki. To Piperi Tavern is a cozy, rustic spot with a classic village-style menu. We ordered a selection of mezze; the whipped feta and tzatziki were standouts, alongside a refreshing Greek salad.

Further afield, popular seafood restaurant Agios Georgios Alamanou is known for its generous platters, piled with prawns, mussels, squid, and crab claws. Ideal for a long, lazy lunch by the sea.

PlusSea, less than an hour from Lefkara, is a high-end beach bar with a polished menu of seaside dishes and craft cocktails. Its red-striped loungers and quiet stretch of sand make it a great spot to refresh in the afternoon heat—in style.

To See

Lefkara corner shop, Eleni is an inviting place to pick up local olive oil, homemade marmalade, and other pantry goods. Don’t miss a visit to the Church of the Holy Cross, which dates back to the 14th century and is said to house a relic of the True Cross. Inside, the towering ceiling is painted with a vibrant starry sky and there is an opulent gilded altar screen.

White Stones is a lesser-known swimming spot along the coast with smooth limestone cliffs and shallow, turquoise waters, 30 minutes from Lefkara.

An hour west of Lefkara, Omodos is a winemaking village tucked into the hills of the Troodos Mountains. Be sure to stop at Oenou Yi Winery for a tasting on the terrace with rolling vineyard views.