By Siobhan Reid

In 1922, on the centennial of Brazil’s independence, a group of trailblazing artists and intellectuals gathered at São Paulo’s Theatro Municipal for a three-day cultural event that would forever change the country’s cultural landscape. The Semana de Arte Moderna (Modern Art Week) brought together art exhibitions, concerts, and poetry readings that rejected European aesthetic traditions in favor of a new national identity rooted in Brazil’s Indigenous, African, and folk heritage.

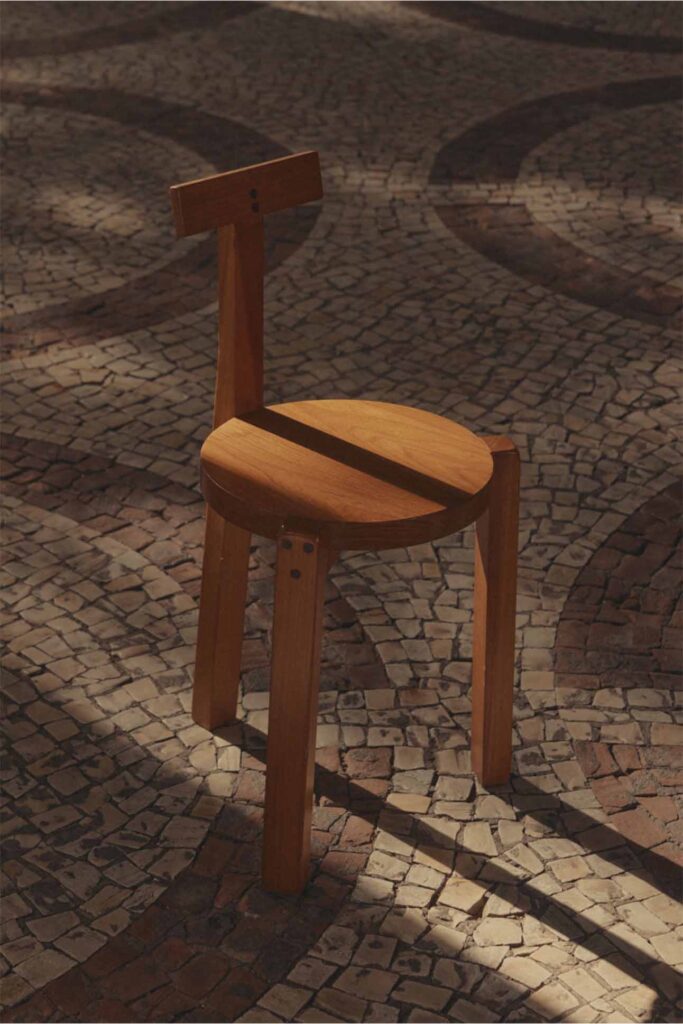

The modernist movement that emerged laid the foundation for the sweeping, sculptural architecture of Oscar Niemeyer, whose curving concrete forms would come to define the urban fabric of Brasília, the country’s capital city. It also gave rise to a parallel tradition in furniture design that put a distinctly Brazilian spin on 20th-century modernism, reinterpreting Bauhaus and other international influences through exquisite natural materials like jacaranda (Brazilian rosewood) and pau ferro (ironwood). More than a century later, these architectural-inspired pieces are now among the most sought-after in the world, regularly commanding five-figure sums at international auctions and galleries.

Thanks to the legacy of the 1922 movement, São Paulo is often considered the cradle of Brazilian Modernist furniture design. A stroll through the upscale streets of Jardim Paulista or Vila Madalena reveals dozens of independent galleries showcasing armchairs, coffee tables, and consoles by masters such as Sergio Rodrigues and Jorge Zalszupin. But it was in Rio de Janeiro where many of these 20th-century designers lived and found inspiration—and for those drawn to the stories behind the objects, the Cidade Maravilhosa (Marvelous City), as the city is often called, offers a more intimate experience, with family-run workshops and unsung dealers keeping the flame of modernism alive.

“São Paulo cemented its status through institutions and collections,” says André Bispo, co-founder of the gallery Legado Rio, “but Rio allowed modernism to breathe.” The street-level space he runs with his partner, Lucas Sales, is located just blocks from the towering palms and orchid gardens of the Jardim Botânico. Inside, the focus is on pieces that reflect how Cariocas live: objects custom-made for the city’s breezy seafront apartments, hillside homes, and lush artist studios. Expect finds by Zalszupin and artist Joaquim Tenreiro, as well as works that emerged from Brazil’s most storied workshops, including Marcenaria Baraúna—a São Paulo-based woodworking studio known for its collaborations with Lina Bo Bardi, among other modernist icons.

On the other side of town, in the bohemian neighborhood of Lapa, adjacent to the brutalist Metropolitan Cathedral of Saint Sebastian, is one of the country’s mainstays of Brazilian modernist design, Mercado Moderno, founded in 2001 by Rosana Vicente, Alberto Vicente, and Marcelo Vasconcellos. Open by appointment only (schedule a time slot via its website or Instagram @memobrazil), the bi-level gallery focuses on original, well-documented pieces—mainly from designers who worked in Rio de Janeiro between the 1950s and ‘70s—that have been carefully restored and contextualized.

For Mercado Moderno collection manager João Vicente, part of what sets Rio’s design scene apart is its artisanal spirit. “While São Paulo is more industrial, Rio has preserved strong ties with neighborhood carpentry shops, family workshops, and a culture of restoration that is still alive today,” he says.

Its team works closely with master carpenters and family-owned workshops in Rio de Janeiro and Petrópolis to carefully restore and reconstruct sought-after designs, such as the iconic Mole and Oscar armchairs from Sergio Rodrigues. One of the biggest challenges, Vicente notes, is sourcing the materials: Many historic works were crafted from now-endangered woods such as jacaranda, which can only be reused if salvaged from demolition or repurposed from original-period pieces. “Fortunately, we still have workshops in Rio where these techniques have been passed down.”

For the Peruvian-born, New York City-based collector Rodrigo Salem—whose Manhattan furniture and decor gallery, Found Collectibles, specializes in Brazilian midcentury-modern pieces—some of the best treasures can be found at Rio’s weekend markets, such as the Rio Antigo Art Fair, Feira Da Praca Luis XV, and Glória Market. Salem advises travelers to bring cash, negotiate within reason, and arrive as early as five or six in the morning, when sellers are just setting up their stalls—“By 10 a.m., all the good pieces are gone,” he says.

He also recommends seeking out some of the smaller furniture stores in Rio’s North Zone, not far from the international airport, as well as in nearby cities such as Teresópolis. It’s in these lesser-visited locales that Salem has scooped up some of his top finds, including a 1960s-era lounge chair by French Brazilian designer Michel Arnoult, discovered amid a pile of old furniture in a wood restorer’s workshop.

“While it can be challenging to hunt around during a holiday, Rio really is a treasure trove,” he says.

To pull back the curtain on the restoration process in the heart of the city, head to Mobix Galeria, where owner and photographer Arthur Cavaliere has transformed a restored colonial townhouse into an emporium for Modernist design. Inside, design objects like vases and wall art share space with impeccably sourced furniture by Zalszupin, Tenreiro, and other midcentury masters. Cavaliere often guides guests upstairs to the second-floor workshop, offering a behind-the-scenes look at the meticulous craft involved in reviving iconic designs, such as the low-slung Petalas table by Zalszupin, its octagonal petals arranged like a blooming flower. With tools on the bench and sawdust on the floor, it’s an environment that gives new energy to a design movement more than a century old—a reminder that, in Rio, Modernism isn’t a relic; it’s still being made.